Last week we were joined by n.e.w.s. contributor Stephen Wright, a Paris-based art theorist, writer, and Editorial Director of the Biennale de Paris who teaches at the European School of the Image, (ÉESI) The Interactive Arts Masters program, University of Pointiers.

Thursday’s marathon seminar was entitled Shadowmapping, which encompassed spy art practices, artistic research as knowledge production, cognitive mapping and the ontology of art in regard to art’s specific use value: it does what no other things do. Once everything could be art… what was the everything? If everything is art, then nothing is and this ontological fate is unique. Art can be both what it is and a proposition of the same thing. What makes something art is the frame, or the specific visibility.

‘Nothing can remain in shadow if it can be mapped. Mapping is a form and technique of attention getting, and since there is little point drawing specific attention to that which is already basking in it, cartographers – like documentary filmmakers – tend to focus on the invisible or barely visible. Yet mapping rarely sees itself as antagonistic to what goes on in the shadows; it fancies itself as aiding the invisible in gaining the visibility it lacks but deserves – as if everything craved attention, and invisibility a deprivation! Does mapping aspire to a perfectly luminescent, shadow-free world? Perhaps — though there is certainly a ways to go in a world shrouded in covert data accumulation and concealed agendas, which is what makes the rise of cognitive-mapping practices over the past decade such a compelling critical by-product of contemporary political and artistic culture. However mapping’s white dream inevitably encounters its own blind spot: for, like all refracting and occluding devices, maps, too, cast shadows.’

‘This particular dialectic of enlightenment has considerable consequences for contemporary art. Indeed cognitive mapping may be seen as contemporary art’s ultimate attempt to save representation, to assert the political potential of mimesis. Increasingly, art practice appears to be moving away from representation toward a regime of redundancy, whereby art does not depict something but is actually at once that something, and a proposition of it: increasingly, art operates on a 1:1 scale. What sorts of mapping projects can be envisaged on this real-life scale? What kinds of contemporary practice are based on data aggregation and how can they themselves be mapped? A little-known text by Lewis Carroll, from 1893, provides an unexpected insight. In Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, Carroll tells of a conversation between the narrator and an outlandish character called “Mein Herr” regarding the largest scale of map “that would be really useful”:

“We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile! (…) It has never been spread out, yet,… the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So now we use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.”

This prescient condensé of the ontological shift underway in contemporary art practice opens three parallel lines of enquiry: 1. How does one go about using the country itself as its own map — ie. what are the conditions of possibility and use of redundancy? 2. Were the farmers right — does such mapping actually shed more shadow than light? 3. What recourse to critical cartography can be envisaged after the end of the regime of representation — a recourse respectful of shadows?’

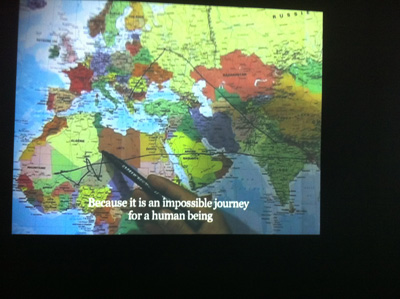

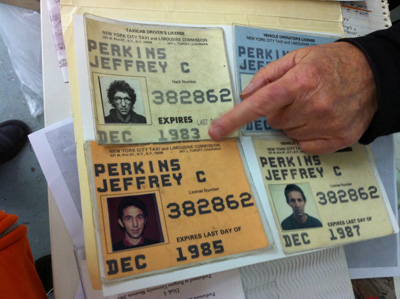

During the course of the day we viewed works by Wikileaks (Collateral Murder); Bouchra Khalili (Mapping Journey,1-8); Till Roeskens (Videocartographies: Aïda, Palestine); Bureau d’études; Francis Alÿs (Sometimes Something Poetic Can Be Political…); aaaaarg.org; pad.ma; Lewis Carroll; Öyvind Fahlström, Jeff Perkins, (Taxi Permits:performative documentation)